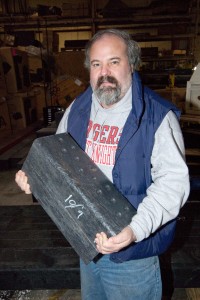

Tom Nosker, a polymer engineer at Rutgers University, has invented a method for turning used plastics into an incredibly strong, durable building material. In Plastic: A Toxic Love Story, I describe how a New Jersey company is using Nosker’s technology to transform used milk jugs and car bumpers into bridges strong enough to hold locomotives or Abrams M-1 tanks weighing thousands of pounds. Nosker’s interest in recycling plastics goes back to the field’s birth in the early 1980s, when faced with growing concern over plastic pollution, the plastics industry set up a center for recycling research at Rutgers. At the time the only business recycling plastic was Wellman Industries, a textiles company that had figured out how to turn PET beverage bottles into polyester fiber. But as Nosker says, “they weren’t telling anyone how they were doing it.” With backing from the industry, Nosker developed a bottle recycling plant and helped set up the country’s first curbside collection program for PET bottles in Highland Park, New Jersey. He’s been looking at ways to give old plastics useful new lives ever since. I talked recently with Nosker about how he came to develop the technology, as well as a new approach to fireproofing plastics:

SF: Why did you get interested in recycling as opposed to working with new plastics?

TN: I saw that people were attacking thermoplastic materials used in packaging. I thought it was ridiculous that people were going to ban the materials when you could melt them and do other things with them. I knew it was an easy thing to tackle – easy in a relative sense. That’s what I decided to spend my life doing.

SF: So you’re making these very strong materials out of plastics like the high- density polyethylene used in milk jugs?

TN: High-density polyethylene (HDPE) is one of the most durable materials in the world made out of a hydrocarbon. Like all thermoplastics, it’s prone to a problem called creep. Which means if you put some stress on it, if it’s a high enough stress, the plastic will change shape as a strict function of time. So you build a picnic table or park bench or bridge or something from it, it will get saggy with time.

SF: Is this the same quality you get with a plastic bag, when you load it up and the handles stretch?

TN: Yeah it’s like that. I had to solve the problem of creep. We had to develop a method to gauge creep, to see if over a few months you can predict how it will behave over 25 years. Then you get to the point of the game, which is to modify the plastic somehow and make it so it’s creep-resistant. HDPE normally creeps at pressures of less than 100 pounds per square inch, which is pretty low — prohibitively low. You could never build a bridge or picnic table or park bench without using some other kind of material in it to take care of that creep issue. So we made composites, different kinds of composites with blends of plastics and fibers.

SF: The bridges you were making were made of milk jugs and car bumpers — and bumpers are made of polypropylene, right?

TN: Fiberglass-filled polypropylene. That’s where the fiber comes in. We chop those bumpers up and we blend that with bottle-grade high-density polyethylene.

SF: And that’s how you get the strength to have it be a bridge?

TN: Yeah. With that composite material I can go to a stress of at least six times or more of what I can do with regular HDPE. I can leave a tank on the bridge for 15 years and drive the tank off and it will go back to its original shape.

SF: Can you do this sort of thing with other of the main packaging plastics, like low- density polyethylene (a film plastic used in baggies) or just plain polypropylene (used in yogurt or margarine tubs)?

TN: I look at each material and think what can I make out of that which would be useful. I would never try to turn low-density polyethylene into a bridge. It’s less stiff than HDPE. It actually belongs in asphalt in my opinion, as an addition to asphalt binder. In fact, there are people that make expensive version of asphalt with virgin low- density polyethylene. Doesn’t that seem like just like falling off a log?

SF: What about polypropylene? What could you make with polypropylene?

TN: Polypropylene can be used to make railroad ties. Railroad ties are big deal in this country. I actually started working on those in 1994. Now there’s 1.25 million recycled plastic railroad ties. And I’ve got a $15 million purchase order from a class one railway somewhere in the United States. We’re working on a much bigger contract with another company that’s maybe 20 times as big. I’m really pleased the technology is taking off.

SF: Could you make a car out of recycled plastic?

TN: Sure, if you can build a bridge, you can build a frame of a car. In some ways I went for making the things thing that were the hardest things to do. That was to make a point — that if you can do what I did, there are a lot of easier things that are like falling off a log. There are a lot of different uses of these different materials and we’re at the beginning of people using them intelligently. There’s a lot of stuff in our waste bin that people in the future will look at as raw material.

SF: What about trying to recycle plastics back into the same products they were before – you know, closing the loop?

TN: People say crazy things like ‘if we don’t close the loop, it’s not recycling.’ That’s baloney. I don’t think its necessary to close the loop. And that’s why I’m doing what I’m doing. I’ve been looking for things that don’t necessarily close the loop but are ways I can create something of really good value so you’re not just landfilling this stuff. (In fact, in the long term, I don’t care if it gets landfilled because one day when plastic recycling is well established, I believe the value of the plastic will be more recognized and people will actually mine landfills for some of the things that are valuable in there. So if it gets stored in landfill for a generation or two, that’s okay. )

You need to think what is the smartest thing to do with this material. And at the end, after you’ve recycled something as many times as you can, if you can close the loop, that’s great. But if you can’t or it doesn’t make sense, or something else makes more sense economically, then just do that. And eventually when you’re done and there’s nothing else to do with the plastic, you can always convert it back to oil or natural gas.

SF: You said you are also doing work on non-toxic flame-retardants?

TN: I have had to develop flame-retardants because people are really nervous about the fact that plastic things burn.

SF: And these are non-brominated fire-retardants?

TN: Absolutely non-brominated. Bromine is a halogen; I don’t use any halogens in my stuff. I use radiation. I have a material in the plastic or the coating of the plastic. When it gets warm it radiates ultraviolent light and that actively removes heat from the flame area so it drops the temperature down. So the plastic may burn, but it’s going to take forever for the plastic to burn up

SF: Could this be used in furniture in place of halogenated fire retardants (which are suspected hormone disrupters)?

TN: Yeah, it could be used for a lot of things.

SF: How come it’s not being used?

TN: I just developed it –this is new stuff! How come there aren’t more plastic bridges out there?

SF: Why not?

TN: Why not? We’re working on it.